The Formation and Evolvement Factors of Urban Villages

Gazetteer of Xin'an County - Map of Xin'an County Territory

Qing Jiaqing | 1819

The last and most comprehensive historical document of the Qing Dynasty, reflecting the historical evolution, geography, politics, economics, culture, prominent figures, customs of Shenzhen and Hong Kong. Compiled by Shu Maoguan and Wang Chongxi, both former Xinan County magistrates, it consists of twenty-three volumes, including chronicles, history, illustrations, mountains and rivers, official positions, military officials, administrative divisions, economic policies, coastal defense, provincial defense, arts and culture, and miscellaneous records. The County Chronicles also include detailed maps titled 'County Boundary Map' and 'Land and Water Map,' illustrating major place names, topography, rivers, forts, and embankments within Xin'an County. The name 'Shenzhen' first appeared in this county chronicle.

Qing Jiaqing | 1819

The last and most comprehensive historical document of the Qing Dynasty, reflecting the historical evolution, geography, politics, economics, culture, prominent figures, customs of Shenzhen and Hong Kong. Compiled by Shu Maoguan and Wang Chongxi, both former Xinan County magistrates, it consists of twenty-three volumes, including chronicles, history, illustrations, mountains and rivers, official positions, military officials, administrative divisions, economic policies, coastal defense, provincial defense, arts and culture, and miscellaneous records. The County Chronicles also include detailed maps titled 'County Boundary Map' and 'Land and Water Map,' illustrating major place names, topography, rivers, forts, and embankments within Xin'an County. The name 'Shenzhen' first appeared in this county chronicle.

Internal Factors

Shenzhen, situated along the Guangdong coastline and neighboring Hong Kong's Kowloon, is a city harmoniously nestled between the mountains and the sea. Its rich urban development history can be traced back over 1700 years. In the 6th year of the Xianhe era of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (331 AD), the Nanhai commandery established the Dongguan commandery, which included six counties, with Bao'an County (now encompassing parts of Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Macau, Zhongshan, Dongguan, and others) as the first one. This marked the inception of administrative divisions in Shenzhen. Both the county seat and the prefectural seat were situated in what is currently Nantou Ancient Town, a place that has since evolved into urban villages. Throughout its history, numerous villages emerged, spreading across the entire region. Natural factors played a fundamental intrinsic role in shaping the overall layout of urban villages in Shenzhen.

According to the Jiaqing Xin'an County Gazetteer annotated in 1819, there were more than 800 villages in Shenzhen at that time. However, as revealed by Liao Honglei, a scholar specializing in Shenzhen's folklore and culture, in the Shenzhen Placename Gazetteer published in 1987, the count had already exceeded 1500 villages by that period.

The relationship between original villages and their environment was usually influenced by natural conditions, with villages strategically located near mountains and water sources, often surrounded and divided by hills, farmland, and water systems. Villages like Hubei, Shuibei, and Xiangxi in the Luohu District were built near water bodies, with villages encircling lakes, and large areas of farmland in the surroundings. Despite the modern urban landscape having obscured the scenes of the past, urban villages still preserve the traits of regional clustering. In areas such as Bao'an and Longgang on the outskirts of Shenzhen today, one can still discover relatively quaint-looking villages.

The formation of village spatial structures is also closely related to the climate in the Lingnan region, known for its humidity, heat, wind, and frequent rain. During the initial settlement, the early settlers prioritized four functions: providing shade, insulating against heat, ensuring proper ventilation, and managing water effectively. As a result, villages in Lingnan generally have higher building density, with streets and lanes characterized by their narrow and closely packed layout.

Furthermore, as urban villages are formed on the basis of primary relationships such as kinship and geographical proximity, residents tend to have a strong sense of local identity. Clan culture is another factor influencing the spatial form in Shenzhen's villages. In many of today's urban villages in Shenzhen, although building materials have been modernized, ancestral halls and archways of the villages are still preserved. For example, in Guimiao New Village, which started demolition and relocation in February 2023, incense continues to burn at the ancestral hall at night.

Shenzhen, situated along the Guangdong coastline and neighboring Hong Kong's Kowloon, is a city harmoniously nestled between the mountains and the sea. Its rich urban development history can be traced back over 1700 years. In the 6th year of the Xianhe era of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (331 AD), the Nanhai commandery established the Dongguan commandery, which included six counties, with Bao'an County (now encompassing parts of Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Macau, Zhongshan, Dongguan, and others) as the first one. This marked the inception of administrative divisions in Shenzhen. Both the county seat and the prefectural seat were situated in what is currently Nantou Ancient Town, a place that has since evolved into urban villages. Throughout its history, numerous villages emerged, spreading across the entire region. Natural factors played a fundamental intrinsic role in shaping the overall layout of urban villages in Shenzhen.

According to the Jiaqing Xin'an County Gazetteer annotated in 1819, there were more than 800 villages in Shenzhen at that time. However, as revealed by Liao Honglei, a scholar specializing in Shenzhen's folklore and culture, in the Shenzhen Placename Gazetteer published in 1987, the count had already exceeded 1500 villages by that period.

The relationship between original villages and their environment was usually influenced by natural conditions, with villages strategically located near mountains and water sources, often surrounded and divided by hills, farmland, and water systems. Villages like Hubei, Shuibei, and Xiangxi in the Luohu District were built near water bodies, with villages encircling lakes, and large areas of farmland in the surroundings. Despite the modern urban landscape having obscured the scenes of the past, urban villages still preserve the traits of regional clustering. In areas such as Bao'an and Longgang on the outskirts of Shenzhen today, one can still discover relatively quaint-looking villages.

The formation of village spatial structures is also closely related to the climate in the Lingnan region, known for its humidity, heat, wind, and frequent rain. During the initial settlement, the early settlers prioritized four functions: providing shade, insulating against heat, ensuring proper ventilation, and managing water effectively. As a result, villages in Lingnan generally have higher building density, with streets and lanes characterized by their narrow and closely packed layout.

Furthermore, as urban villages are formed on the basis of primary relationships such as kinship and geographical proximity, residents tend to have a strong sense of local identity. Clan culture is another factor influencing the spatial form in Shenzhen's villages. In many of today's urban villages in Shenzhen, although building materials have been modernized, ancestral halls and archways of the villages are still preserved. For example, in Guimiao New Village, which started demolition and relocation in February 2023, incense continues to burn at the ancestral hall at night.

After the founding of the People's Republic of China, the country entered a period of modernization where it borrowed elements from the Soviet-style centrally planned economy and collectivist model in terms of ideology, politics, and economics, with industrialization as the primary goal for resource allocation. Between 1949 and 1979, due to its unique geographical location, Bao'an County was considered by the government as the front line near capitalism, and villagers were not allowed to freely travel between Bao'an and Hong Kong. It was only on March 5, 1979, when the State Council officially approved the transformation of Bao'an County into Shenzhen City and designated 327.5 square kilometers of land as an economic special zone in 1980. It became an "experimental field" for reform and opening-up and a "window" for attracting foreign investment, marking the beginning of large-scale urban development.1

In this context, the city rapidly expanded, and the transformation of land use for urban construction became one of the external factors driving changes in the spatial characteristics of urban villages in Shenzhen. With domestic and foreign investments pouring into Shenzhen, the demand for construction land continuously increased, with most of the land being taken from agricultural land acquired from farmers by the government, leading to a simultaneous rapid decrease in ecological land. After two rounds of rural urbanization reforms in 1992 and 2004, Shenzhen became the "first city in China without rural areas." In 1992, it declared comprehensive urbanization of the special zone, and by the end of 2004, it announced the cancellation of agricultural household registration2, abolished rural administrative institutions and management systems, allowing the remaining 270,000 farmers to "leave the countryside and work in the city," and completed the transformation of land ownership to state ownership while retaining land use rights under collective ownership.3

In addition to the transformation of urban construction land and land conversion, changes in population structure and industrial structure have also given rise to the evolution of spatial forms in Shenzhen's urban villages. As farmers lost their arable land and could no longer engage in traditional agricultural activities, they ingeniously utilized the compensation received for their land and the geographical advantage of proximity to Hong Kong to venture into economic activities, adapting to their new living environment and opportunities. For example, they established joint ventures and collaborated with external investors, as well as initiated "Three-Plus-One" trading-mix enterprises (custom manufacturing with materials, designs or samples supplied and compensation trade), providing various services and goods to the city. This fostered economic diversification within the special zone and promoted the urbanization process. With the advancement of special zone development, the secondary industry experienced remarkable growth, leading to a direct increase in the employed labor force.

Starting from the 1980s, the government in Shenzhen introduced a series of policies that laid the foundation for the city to become a hub for immigration. In 1983, the "Interim Measures for the Implementation of Labor Contracts in Shenzhen" were enacted, making Shenzhen the first city in mainland China to implement a labor contract system. This provided a relatively stable contract guarantee for labor, attracting a large number of rural migrant workers and external laborers to seek employment opportunities there. Shortly thereafter, in 1985, the "Interim Regulations on the Management of Temporary Residence Permits in Shenzhen Special Economic Zone" introduced the temporary residence permit system, allowing residents in Shenzhen to obtain more convenient residential identity verification, encouraging people to move to Shenzhen. In 1989, millions of laborers flooded into Shenzhen, with a significant labor force contributing to the city's construction and production. This influx marked a unique wave of immigration, and Shenzhen became one of the earliest cities to attract laborers from all over the country.4

In this context, the city rapidly expanded, and the transformation of land use for urban construction became one of the external factors driving changes in the spatial characteristics of urban villages in Shenzhen. With domestic and foreign investments pouring into Shenzhen, the demand for construction land continuously increased, with most of the land being taken from agricultural land acquired from farmers by the government, leading to a simultaneous rapid decrease in ecological land. After two rounds of rural urbanization reforms in 1992 and 2004, Shenzhen became the "first city in China without rural areas." In 1992, it declared comprehensive urbanization of the special zone, and by the end of 2004, it announced the cancellation of agricultural household registration2, abolished rural administrative institutions and management systems, allowing the remaining 270,000 farmers to "leave the countryside and work in the city," and completed the transformation of land ownership to state ownership while retaining land use rights under collective ownership.3

In addition to the transformation of urban construction land and land conversion, changes in population structure and industrial structure have also given rise to the evolution of spatial forms in Shenzhen's urban villages. As farmers lost their arable land and could no longer engage in traditional agricultural activities, they ingeniously utilized the compensation received for their land and the geographical advantage of proximity to Hong Kong to venture into economic activities, adapting to their new living environment and opportunities. For example, they established joint ventures and collaborated with external investors, as well as initiated "Three-Plus-One" trading-mix enterprises (custom manufacturing with materials, designs or samples supplied and compensation trade), providing various services and goods to the city. This fostered economic diversification within the special zone and promoted the urbanization process. With the advancement of special zone development, the secondary industry experienced remarkable growth, leading to a direct increase in the employed labor force.

Starting from the 1980s, the government in Shenzhen introduced a series of policies that laid the foundation for the city to become a hub for immigration. In 1983, the "Interim Measures for the Implementation of Labor Contracts in Shenzhen" were enacted, making Shenzhen the first city in mainland China to implement a labor contract system. This provided a relatively stable contract guarantee for labor, attracting a large number of rural migrant workers and external laborers to seek employment opportunities there. Shortly thereafter, in 1985, the "Interim Regulations on the Management of Temporary Residence Permits in Shenzhen Special Economic Zone" introduced the temporary residence permit system, allowing residents in Shenzhen to obtain more convenient residential identity verification, encouraging people to move to Shenzhen. In 1989, millions of laborers flooded into Shenzhen, with a significant labor force contributing to the city's construction and production. This influx marked a unique wave of immigration, and Shenzhen became one of the earliest cities to attract laborers from all over the country.4

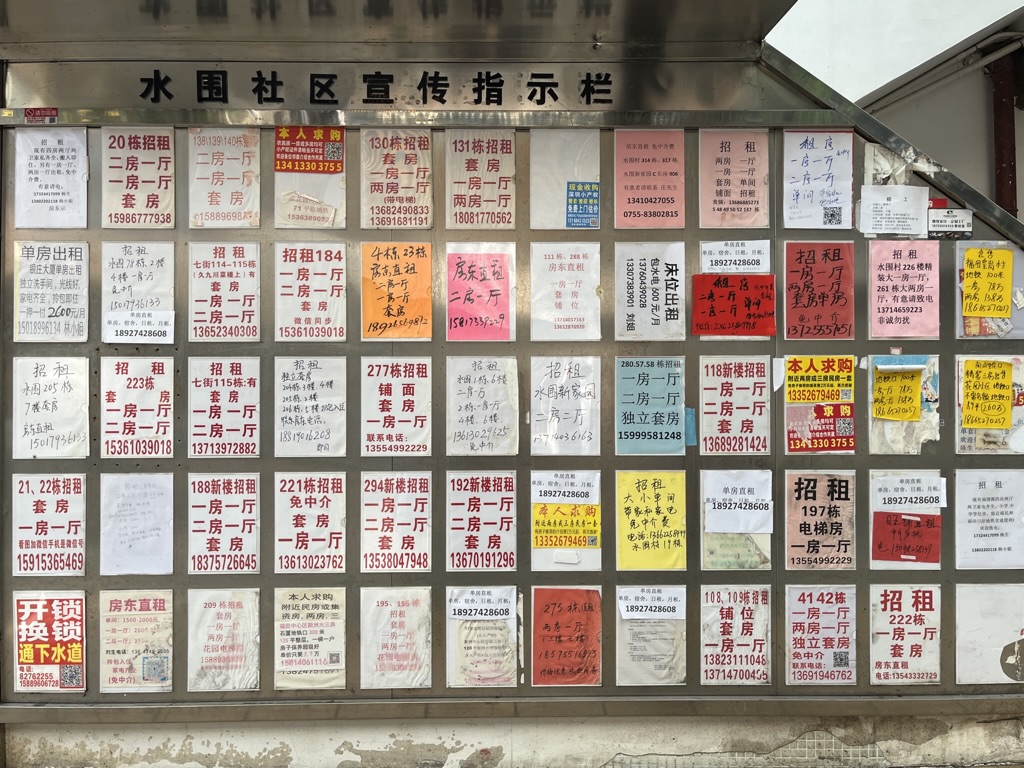

The rapid population growth directly increased the demand for housing, public facilities, municipal infrastructure, and more. In Shenzhen, a city characterized by high population mobility, affordable rental housing, often in the form of low-cost housing, became the preferred choice for floating populations. However, the government, while focusing on economic development, overlooked the housing needs of these populations. Additionally, inadequate predictions of population growth rates resulted in an imbalance in the housing supply structure.

Driven by economic interests, various interest groups, including villages and towns, began to illegally occupy, transfer, or trade land and construct private housing units. These self-built homes by farmers happened to fill the gap in the housing supply in the market. Simultaneously, they provided significant economic benefits to the farmers and became one of the main sources of their income. Gradually, this gave rise to the unique urban spaces later referred to as "urban villages."

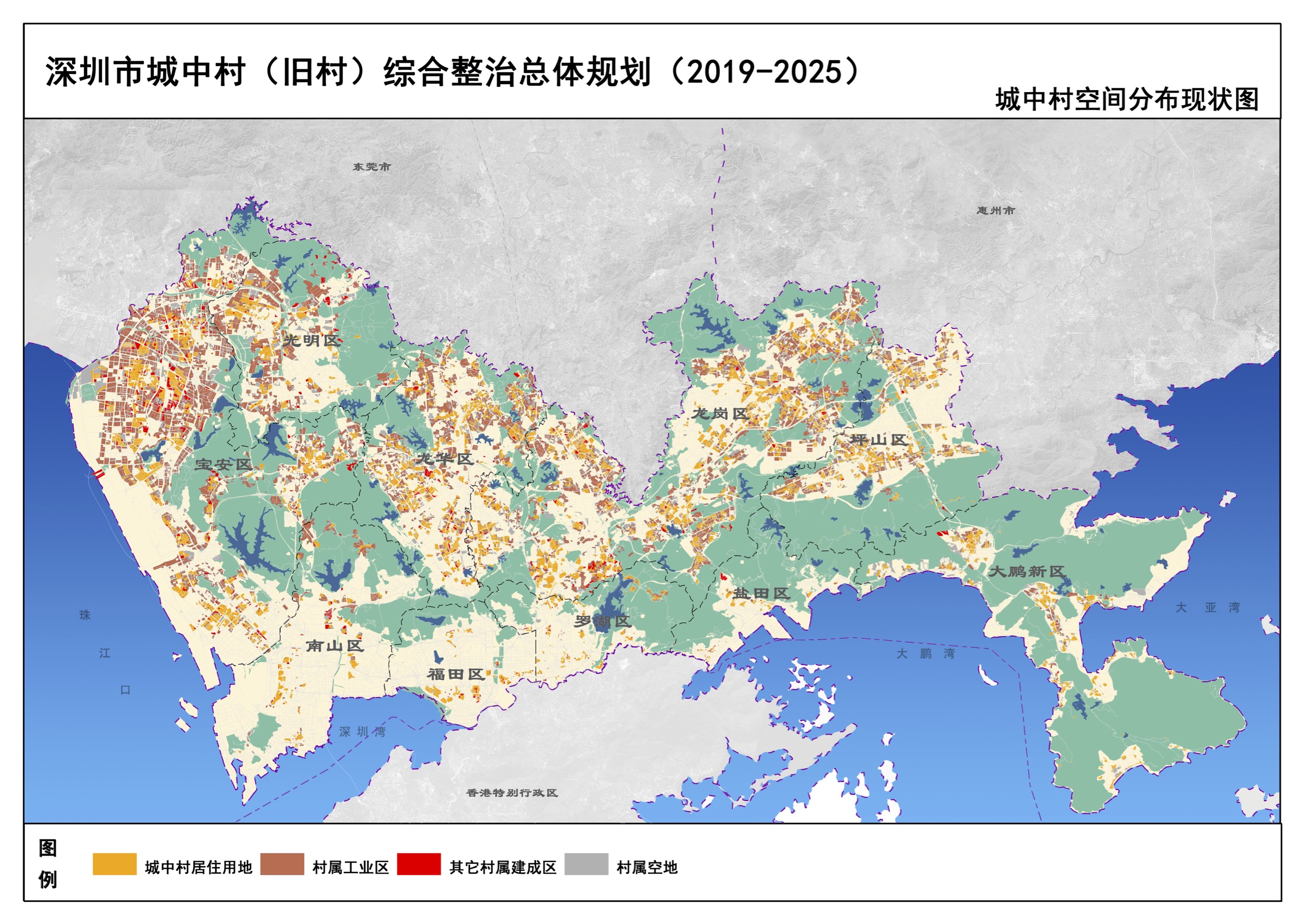

According to the "Comprehensive Renovation Master Plan for Shenzhen Urban Villages (Old Villages) (2019-2025)" issued by the Shenzhen Urban Planning and Natural Resources Bureau in 2019, the total land area of Shenzhen's urban villages is approximately 320 square kilometers, accounting for 31% of the city's construction land. These urban villages are organized based on administrative villages, totaling about 336 (with 91 administrative villages within the special economic zone), and they consist of 1,044 natural villages (with one or more natural villages forming an administrative village). There are over 350,000 rural and privately self-built houses, comprising 43% of the city's total building volume, and they are home to approximately 60% of the city's actual population.

How did the scale of Shenzhen's urban villages gradually expand? What evolvements occurred in terms of social space, economic space, and spatial morphology? Many scholars, architects, and artists have explored these changes and the underlying causes in depth. In the next article, we plan to share insights into the ones of the architectural spatial forms within urban villages, drawing from both existing research and our field observations.

Driven by economic interests, various interest groups, including villages and towns, began to illegally occupy, transfer, or trade land and construct private housing units. These self-built homes by farmers happened to fill the gap in the housing supply in the market. Simultaneously, they provided significant economic benefits to the farmers and became one of the main sources of their income. Gradually, this gave rise to the unique urban spaces later referred to as "urban villages."

According to the "Comprehensive Renovation Master Plan for Shenzhen Urban Villages (Old Villages) (2019-2025)" issued by the Shenzhen Urban Planning and Natural Resources Bureau in 2019, the total land area of Shenzhen's urban villages is approximately 320 square kilometers, accounting for 31% of the city's construction land. These urban villages are organized based on administrative villages, totaling about 336 (with 91 administrative villages within the special economic zone), and they consist of 1,044 natural villages (with one or more natural villages forming an administrative village). There are over 350,000 rural and privately self-built houses, comprising 43% of the city's total building volume, and they are home to approximately 60% of the city's actual population.

How did the scale of Shenzhen's urban villages gradually expand? What evolvements occurred in terms of social space, economic space, and spatial morphology? Many scholars, architects, and artists have explored these changes and the underlying causes in depth. In the next article, we plan to share insights into the ones of the architectural spatial forms within urban villages, drawing from both existing research and our field observations.

Footnotes:

1. Ma, H. and Wang, Y. (2011) The Space Evolvement and Integration of Villages in Shenzhen. Beijing: Intellectual Property Publishing House.

2. The household registration (Hukou) system implemented since 1958 initially tightly restricted population mobility. It was a family-based population management policy aimed at ensuring the sequence of "urbanization before ruralization," preventing blind increases in urban labor force and blind outflows of rural labor.

3. Under the dual land system for urban and rural areas, urban land is owned by the state, while rural land belongs to the village collectives. The village collectives allocate homesteads and agricultural land based on the needs of each household, but these lands cannot freely circulate in the market as commodities. They cannot be transferred, sold, or used for non-agricultural construction.

4. Xiao, J. and Chen, D. (2022) Image-History-City: Shenzhen’s Changing and Reshaping Since 1891, China Ethnic Culture Press.

1. Ma, H. and Wang, Y. (2011) The Space Evolvement and Integration of Villages in Shenzhen. Beijing: Intellectual Property Publishing House.

2. The household registration (Hukou) system implemented since 1958 initially tightly restricted population mobility. It was a family-based population management policy aimed at ensuring the sequence of "urbanization before ruralization," preventing blind increases in urban labor force and blind outflows of rural labor.

3. Under the dual land system for urban and rural areas, urban land is owned by the state, while rural land belongs to the village collectives. The village collectives allocate homesteads and agricultural land based on the needs of each household, but these lands cannot freely circulate in the market as commodities. They cannot be transferred, sold, or used for non-agricultural construction.

4. Xiao, J. and Chen, D. (2022) Image-History-City: Shenzhen’s Changing and Reshaping Since 1891, China Ethnic Culture Press.