Urban Villages: A Microcosm from 'Demolition' to Coexistence

Urban villages[1], or more commonly known in China as "城中村" (chengzhongcun), literally translated as "villages-in-the-city", are a social phenomenon resulting from the rapid urbanisation of China since Deng's reform, which gradually escalated from the beginning of the 1980s. Many urban villages still exist throughout major cities in China, with Shenzhen having the largest number of them in the country.

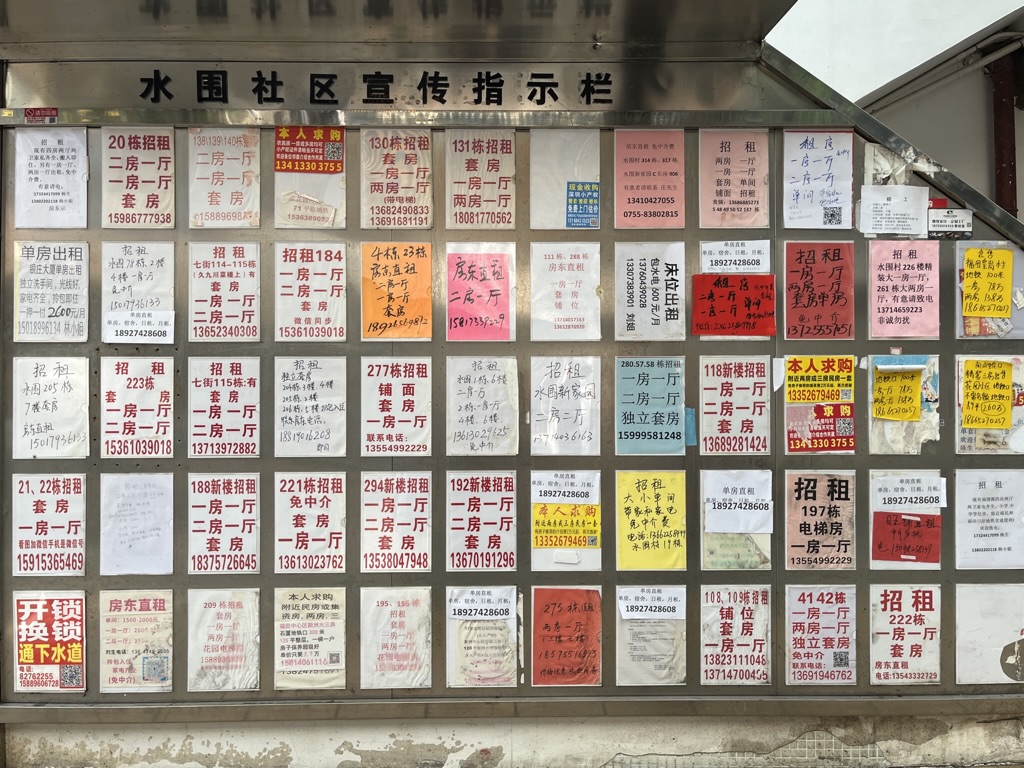

Superficially, in Shenzhen, the idiosyncrasies of urban villages lie not only in their geographical locations in or near the city centre but also in the spatiality that strongly contrasts with the surrounding urban environment. Especially following the COVID-19 lockdowns, actual gates and tripod turnstiles were established to control, manage, and curb population flow, enclosing and separating many urban villages from adjacent main streets. As such, these physical characteristics produce perceivable thresholds; once you cross these 'borders', you seem to enter spaces what Foucault called heterotopia. However, urban villages are also ordinary in everyday life, as they are the pervasive architectural form dominating the city, with their evolution inextricably linked to the developmental history of Shenzhen municipality, past and present.

Since Deng's reform, self-constructed and managed urban villages in Shenzhen have provided affordable housing and accommodated millions of migrant workers. As unique social spaces that were previously not incorporated into the urban administrative and state apparatus, urban villages have attracted constant attention from the government and have been debated and studied as problems of urban security and governance. Initially, the official narrative pathologised urban villages as 'city cancers', urban hotbeds for crime and disorder, backward and filthy places that must be purged, legitimising repressive actions of forced demolition and eviction[2]. This technique of governance is commonly known in China as 'cut at one stroke', referring to the unreserved removal and construction as a means of cosmetic surgery for urban landscapes aspiring to modernity. Thus, China is also given the moniker "拆那" (chai na), literally meaning 'razing there'.

Unsurprisingly, the massive de-reconstruction of urban villages has inevitably led to controversies and protests, critiquing the dogmatic urban planning and repressive policies, and their consequences of social and spatial injustice, urban inequalities, and dispossession of migrant workers' rights to the city.

The year 2016 signifies a shift in urban planning strategy regarding the redevelopment of urban villages, indicating that while urban villages in the outer districts should continue to be demolished, those in the inner districts should be preserved, upgraded, and integrated into the urban environment[3]. However, as Cindi Katz (1998) noted, 'preserving' urban space does not typically mean prolonging their existence but rather purging them of their undesirable and disorderly aspects, thus polishing and sanitising space with an appealing narrative, burying the labour, messiness, and conflicts that once produced and defined the space.

Subsequently, the theme of the 2017 Bi-City Biennale of UrbanismArchitecture (UABB)[4] is established as 'Cities, Grow in Difference' (城市共生), advocating the government's new vision of urban villages' values in future, more sustainable urban development. However, the precise implications of 'growing in difference' remain uncertain. The Chinese term “共生”, directly translated as symbiosis, suggests that urban villages have become rather chummy with Shenzhen's future vision.

But drawing on Raymond Williams, "cities, growing in difference" can also hint at a sly manoeuvre wherein dominant powers charmingly embrace elements of opposition, assimilate and co-opt resistance and difference[5]. Within this frame, rather than giving urban discrepancies the boot, Shenzhen's government has employed an alternative strategy to corral and harmonise these differences, neatly packaging what Lefebvre would term ‘maximal difference’ into tidier, more palatable ‘minimal differences’.

According to Lefebvre's musings on differential space, it's vital to discern between these maximal and minimal differences if one hopes to fathom the mechanics of urban space and the thrilling potential for change. Lefebvre wasn’t one to see differences as mere particularities or diversities. No, he saw them as the very forces producing and shaping the space of an [urban society]; thus, as productive forces. To him, urban space isn’t just a motley collection of differences. It's a pulsing, dynamic entity, generated and driven by these maximal differences - akin to the energising spark one finds in a brilliant piece of art – indicating the potential of something new could be surprisingly generated by the contradictory encounters between different modes of living and ways of everyday life. In contrast, minimal differences contribute to the maintenance of existing social structures and systems.

To paint a vivid picture, let's delve into one official tale of differential space. From which, one can discern that in Shenzhen, bulldozers are as steadfast as British "sorry" etiquette, even as the city's official spiel about urban villages has undergone a makeover. Once dismissed as 'grubby, tumultuous, and rather behind the times', urban villages now enjoy a revered status, heralded as the very heart and soul of Shenzhen's rich tapestry of history, memory, and culture.

Yet, amidst the flowery prose, what is happening here is a curious exercise in selective preservation. Urban villages are clinically carved out as 'up for grabs' spaces, earmarked for a modicum of cultural preservation, which allows the continuing of capital accumulation through 'spatial fix' in the tug-of-war of negotiation between villages, the government, and the private developers.

Shuiwei Village 水围村

Nestled in the heart of Shenzhen's Futian district, the Shuiwei village stands as a model of urban village reconstruction, according to the official narrative:

水围村,一个“创新之城中村”的蝶变故事。

The reborn story of Shuiwei village, an innovative village within a city.

“中国式现代化”的深圳探索微观范本。

A micromodel of Chinese-style modernisation exploration in Shenzhen.

From its 'handshake buildings' now repurposed to house the city's brightest talents, to the vast spaces that once stood, which have since been transformed into a plaza accompanied by indispensable public amenities such as a library; a significant portion was transfigured into the Shuiwei 1368 cultural district [6]. This case is promulgated as the exemplary model for the subsequent urban renewal, as Shenzhen Business Daily (深圳商报) reported (2021):

"Urban villages provide a fascinating glimpse into Shenzhen's urban progression and are indicative of the city's level of civilisation. Situated in the premium locale of the Futian Central District, the historically rich Shuiwei Village, with a lineage spanning over six centuries, has emerged as the epitome of modern urban village civilisation. The inception of cultural and sports facilities has elevated these urban villages to civilised 'urban attractions'. The Shuiwei 1368 cultural district, epitomising the Village's transformation, charts a fresh trajectory in Shenzhen's urban renewal narrative. It seamlessly marries the village's rich cultural tapestry from the urban-rural reform era with a touch of international-standard construction." (My translation)

However, the evolution of Shuiwei can be discerned as a nuanced 'social translation' of value, knowledge, and ideology. As Lefebvre poignantly put in 'Right to the City' (p.99), "space in itself may be primordially given, but the organisation, and meaning of space is a product of social translation, transformation, and experience." This intricate process has seen the erstwhile rural enclave reimagined into a contemporary urban haven, epitomising civilisation. This vision is immortalised in bronze statues and vividly reflected in the eclectic restaurant signs. Intriguingly, this transformation wasn't achieved by bluntly replacing the traditional (rural) with the modern (urban). It was nuanced, echoing the principles of 'racial capitalism', a framework that delineates both human and non-human interactions and demarcates social space-time for value extraction.

Bhattacharyya (2018, p.9) posits that racial capitalism isn't a monolithic theory of racism with a distinct history preceding capitalism, nor is it a rigid categorisation of race. Instead, the "racial" in racial capitalism signifies its function: to differentiate rather than homogenise, drawing lines between the formal and informal, the productive and unproductive, and the biopolis and necropolis. Racial capitalism is emblematic of a social structure that thrives on coercive power, individual aspirations, and the regimentation of bodies and the demarcation of social space-time. The 'racial' facet illuminates that the bedrock of contemporary global capitalism is a rich tapestry of diverse (though often discriminated against) social relationships and multiple layers of social space-time. Differences of spaces are more of a necessity than appendage, yet simultaneously must be constantly reduced to the ‘minimal’. The Shuiwei 1368 cultural district, with its melange of global cuisines and foods from all over China, is an urban epicurean delight, yet it evokes a nostalgia that's distinctly un-Shuiwei.

Footnotes

[1] It is worth noting that the English translation "urban villages" is not without problems, as the term has its own specific history, meaning, and context in the West. See ["城中村",名字的原真性]

[2] See Foreword in O’Donnell, M.A., Wong, W. and Bach, J. (2017) Learning from Shenzhen: China’s Post-Mao Experiment from Special Zone to Model City. University of Chicago Press.

[3] The establishment of the SEZ in areas bordering Hong Kong created an exceptional zone within socialist China. Internal borders and checkpoints were set up to separate the SEZ from the rest of Shenzhen, closer to mainland China. This border was known as "the second line," in contrast to the Sino-British border, referred to as "the first line." The areas between the first and second lines were called "the inner districts" (guannei 关内), comprising present-day Nanshan(南山), Futian(福田), Luohu(罗湖), and Yantian(盐田), while the areas beyond the second line were called "the outer districts" (guanwai 关外).

[4] UABB is currently the only biennial exhibition in the world exclusively on the themes of urbanism and urbanisation.

[5] See Shmuely, ‘Totality, Hegemony, Difference’; Williams, Marxism and Literature.

[6] The village is renamed as Shuiwei 1368 because it is said that 1368 is the founding year of the village.

Reference

Bhattacharyya, G. (2018) Rethinking Racial Capitalism: Questions of Reproduction and Survival. Rowman & Littlefield International, Limited.

Katz, C. (1998) ‘Excavating the Hidden City of Social Reproduction: A Commentary’, City & Society, 10(1), pp. 37–46. Available at here︎︎︎

Lefebvre, H. (1991) The production of space. Oxford, OX, UK ; Cambridge, Mass., USA: Blackwell.

Lefebvre, H., Kofman, E. and Lebas, E. (1996) Writings on cities. Cambridge, Mass, USA: Blackwell Publishers.

Yang, R. (2021) 福田区水围社区打造新时代城中村文明典范 (Futian District Shuiwei Community creates a civilised model of urban village in the new era). Available at here (Accessed: 19 April 2023).